Are we pushers or prescribers? Proposing a diagnostic model for IC

By

— February 11th, 2021

In my last blog, I took the stance that internal communication is not a profession because there is no established body of content or model of practice that forms the foundation for licensure, and that licensure is not necessary to practice communications.

Even if we don’t want to go the route of licensure, many of us do want our clients and sponsors to recognize our specialized expertise, and to understand that we don’t merely operate on creative hunches.

One of the essential building blocks of any professional practice model is a set of diagnostic methods for selecting interventions, and guidelines for implementing interventions based on scientifically-derived evidence.

Beating change fatigue: How to recharge embattled employees for 2021

If only communications were as simple as getting a specific reading on a blood test and then looking to a guidebook to determine what to prescribe!

However, there certainly could be a generally-accepted model for how to analyze the underlying cause of a business problem and developing the best possible communications solution – if indeed communications is the right domain of the solution.

I’ve scoured textbooks and professional manuals for models of communication analysis and most of them go something like this:

- Situation analysis

- Audience/stakeholder analysis

- Develop specific goals and objectives

- Develop tactics for message design and choice of media

- Build a budget and project management plan

- Measure the outcome

This is not a diagnostic model – it’s a project management model. It assumes that we have the right set of tools and skills to fix the problem, so we immediately jump into responding to the client’s identified problem and solution.

That’s like someone saying to their physician, “Please write a prescription for 75 mg of superpharm painkiller– and I’d like it by 10:00 today at and a price of under $10.”

I daresay any physician who would simply comply with that request without some kind of examination is a “pusher” and not a “prescriber”.

I use a practice model called performance consulting, the foundation of which was developed by expert practitioners and academics in training and organizational behavior.

Here’s a real example of a request I got from the VP of HR in a large utility company: Supervisors were rating almost all of their subordinates as excellent in the new performance management system, and the client wanted us to produce a training video on how to fill out the rating form correctly.

I used my version of the performance analysis model (CommAdd) to rather quickly do a diagnosis.

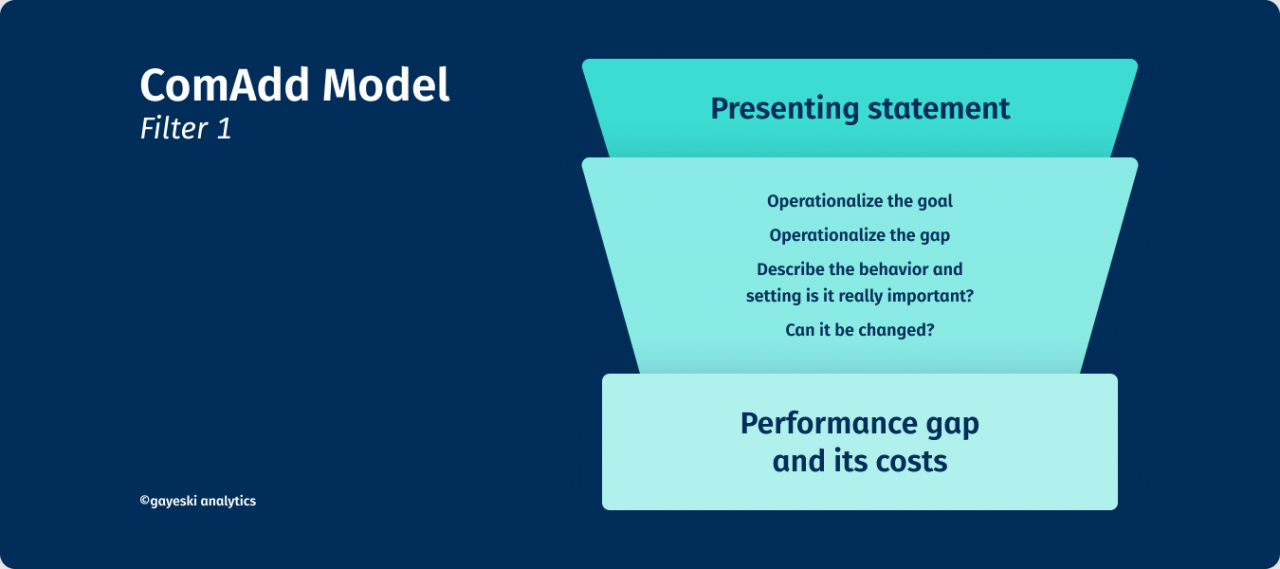

Think of the diagnostic process as a filter – you start out with a vague “presenting statement” from a client, and then try to ask questions that let you identify the performance gap and its cost to see if it’s worth pursuing.

We learned that about 90% of the performance evals were filled out with “excellent” ratings, but the client really couldn’t tell me what the cost of this gap was other than they were giving out too many raises and were tolerating some poor performers.

We estimated that this might cost the utility $100k in undeserved raises and likely impacted the morale of excellent performers. OK – now it was clear that we’d need to be able to produce a solution that cost significantly less than $100k - if indeed we thought we could change the behavior.

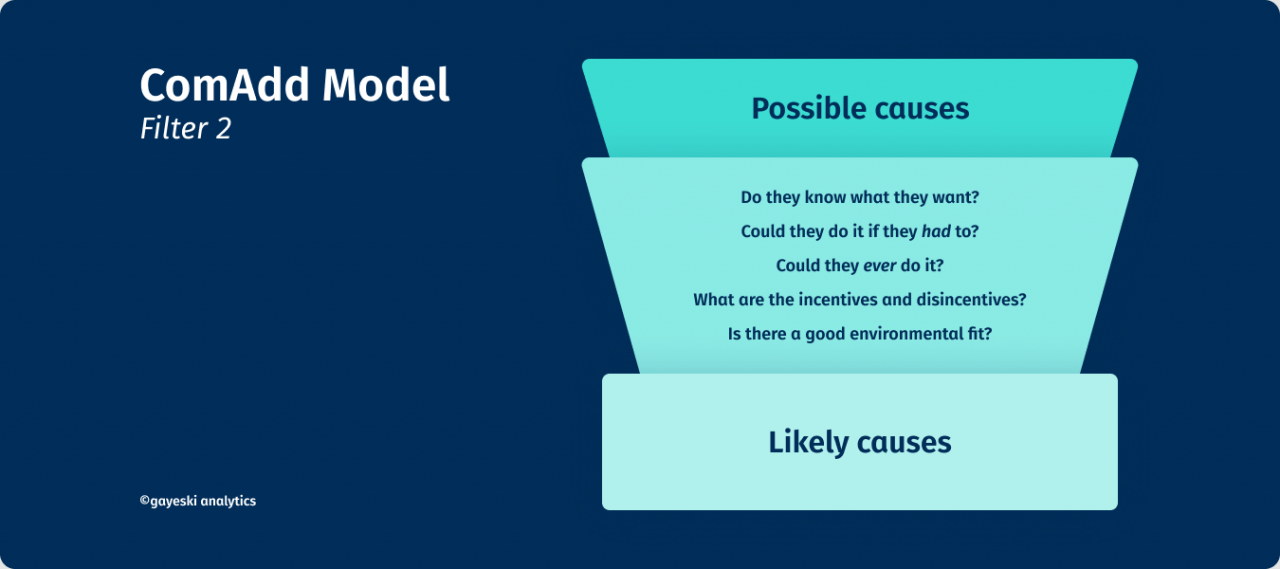

In the second filter, we look at possible causes for the problem.

It might be as simple as supervisors not knowing what you want them to do. Maybe sending a memo saying that management expects that no more than 30% of employees get ‘excellent’ ratings would work.

But when we did some focus groups, supervisors told us that giving employees below-average ratings only made them sulk, and that HR made it almost impossible to get rid of an employee.

It was actually easier to give a problem subordinate a great rating and hope that they could be passed off to some other unsuspecting supervisor or company -- so there were actually some important disincentives to doing the ratings as desired by management.

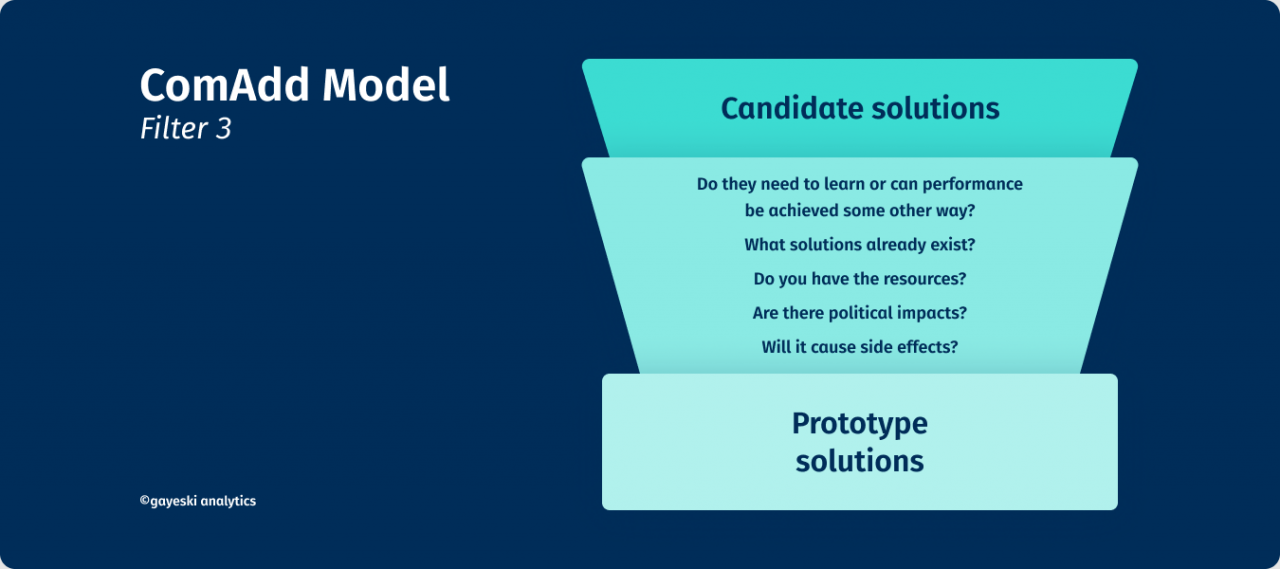

Now we know that a training video on how to fill out a performance evaluation form would be useless. We recommended to the client a different set of interventions:

- A short inexpensive video that highlighted examples of supervisors in the company who had confronted employees who were performing poorly, how they approached it, and how in fact they found in some cases they were able to help employees who were experiencing health or other crises in their lives or to be able to recommend paths to different kinds of jobs that were more suitable.

- We changed the performance rating form to allow supervisors to better describe employees’ goals and challenges and took away the stigma of having to give “grades” to their subordinates.

- We recommended that management provide a limited budget for raises, and to evaluate supervisors on the way that they were developing and coaching their employees, so that performance evaluations were seen not just as punishment but as a way of developing the workforce. We developed a small bonus plan for supervisors who used these tools effectively to develop and re-position employees in their areas and who worked across business units to place employees in jobs that best matched their interests and skills. We wanted to be careful to not create more problems than we were solving.

NOT what the client came in expecting – but a set of interventions that really did have an impact. I almost never give clients what they came in thinking they wanted – and that’s ok.

They now recognize my value as a diagnostician and equal strategic partner. I believe that if we as a profession adopted a similar diagnostic model, that clients would recognize that we do have a standardized, logical method of practice – AND that we are not just order-takers.

But we also should not be afraid to own the badge of creativity, because our professional magic is a blend of purposeful diagnosis, implementation of research-based solutions, and the development of engaging and novel ways to capture the human emotion and intellect.

- Next week on Thursday, February 18th, Diane Gayeski's final blog in this series proposes a new model for assessing Internal Communications.