Why true allyship matters – and what's really changed since the BLM protests

By

— March 22nd, 2021

I could sense the uncomfortable silence.

People were awkwardly shuffling around, trying to avoid eye contact with me. Five minutes ago, we’d all been laughing and joking about what we were going to do at the weekend. Now you could cut the tension with a knife.

My heart was racing, and I couldn’t stand the sympathetic looks, so as usual, when these situations occurred, I turned to the group and said: “Anyway, what were you saying about that restaurant?”

It was 2011, and I was working as an Internal Communications Manager for a mental health service. I’d volunteered to support our “It’s good to talk!” campaign, which involved standing in my local shopping center handing out leaflets, encouraging people to talk about Mental Health.

Midway through our chatter, as we were handing out our leaflets, two young boys walked past and shouted, “Urgh can you smell something? I bet it’s that dirty p*ki.”

The boys stood at a distance, waiting for my reaction. I didn’t look up, and instead, I glanced at my colleagues who stood next to me. The two boys ran off laughing, and I waited to see if anyone would say something. They didn’t.

Racism, diversity, and inclusion in the workplace: It's time to get uncomfortable, to get comfortable

Why allyship matters

As someone who is often underrepresented in the organizations I have worked in, I’ve never wanted anyone to feel uncomfortable in my presence, so I always over-compensated and often ignored the situation or made jokes to make others feel comfortable.

I knew these colleagues were kind and generous people. We’d all spoken passionately about the unfair treatment of underrepresented people.

But when it came to stepping up in a time of need, they struggled to know what to say and looked to me to reassure them.

This isn’t a unique situation. I know many others who have faced similar interactions at work. The awkwardness, the uncomfortable laughter, the silence when someone remarks or says something that singles you out because you look different from everyone else.

When I looked up the term ally, I came across Amnesty International’s definition:

“An ally is someone who takes action to support a group that they are not part of. They develop strong ties to that group while remembering they are there in a supportive role. They know to turn up when needed and when to take a step back, never taking the spotlight.

“Allies are not saviors, they know the people they are supporting can raise themselves up. They champion the needs of that group’s voice. An ally is an advocate within their own group’s to tackle ignorance and getting more to become allies.”

The performative allyship trap

Performative allyship, on the other hand, can be toxic and dangerous. When George Floyd was tragically murdered and the Black Lives Matter protests started, my inbox was flooded with emails from CEOs who had released statements to say that they would review their policies and use their platform to make a difference.

But if you go back through the organizations who released these messages, how many of them have done something that has made a real difference?

How many organizations have genuinely looked at their recruitment policy and thought about how bias plays a part in their culture? How many organizations have encouraged their colleagues to speak up against unfair treatment and reassured them that they’d be no consequences for doing so?

How many have said that if any of their people represent their organization at an event, they have to ensure that the speaker list is representative, not only in terms of race but other protective characteristics as well?

Not many, I fear.

Even looking at our own communications industry, I’ve seen five industry events take place with limited or no representation on their speaker list in the last three months alone.

Most of the folks speaking are from large corporate organizations whose CEOs wrote those statements. But yet their communication leads, the people who are integral to supporting change, are speaking at events where organizers have chosen to ignore certain groups of people.

When questioned, there are tumbleweed moments from the same people who only nine months previously were professing their support online, posting black squares and claiming that they were ‘listening’ and ‘reading’ to understand more.

I received messages from presenters who were speaking at the event who felt I was being unfair for calling them out. But on the other side, I received messages from marginalized people who felt scared to speak up in case it ruined their chances for future speaking opportunities or promotions as they feared being seen as troublemakers.

But imagine how empowered they would have felt if ‘allies’ had come forward and said: “We stand with you, and this is unacceptable.”

I often wonder what would have happened that day if my colleagues became allies and reported the incident. Would I have been less scared walking to my car after my shift had finished?

Would I have lifted my head and walked proudly into future events without the fear of something like that happening again? Would I have stood up for my right to belong sooner?

Recognizing my privilege

I’m an internal communicator. I never intended to speak about diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging as much as I have in recent months, and I don’t claim to be an expert in every area of this work.

But I acknowledge that I have a platform and a supportive community, and a certain level of privilege compared to others.

Privilege is a word that can trigger lots of people as they associate it with wealth. That’s not the case. Wealth is one aspect but not the full spectrum of privilege. It’s important to be very clear of your privilege because that will make a difference in how you interact as an ally.

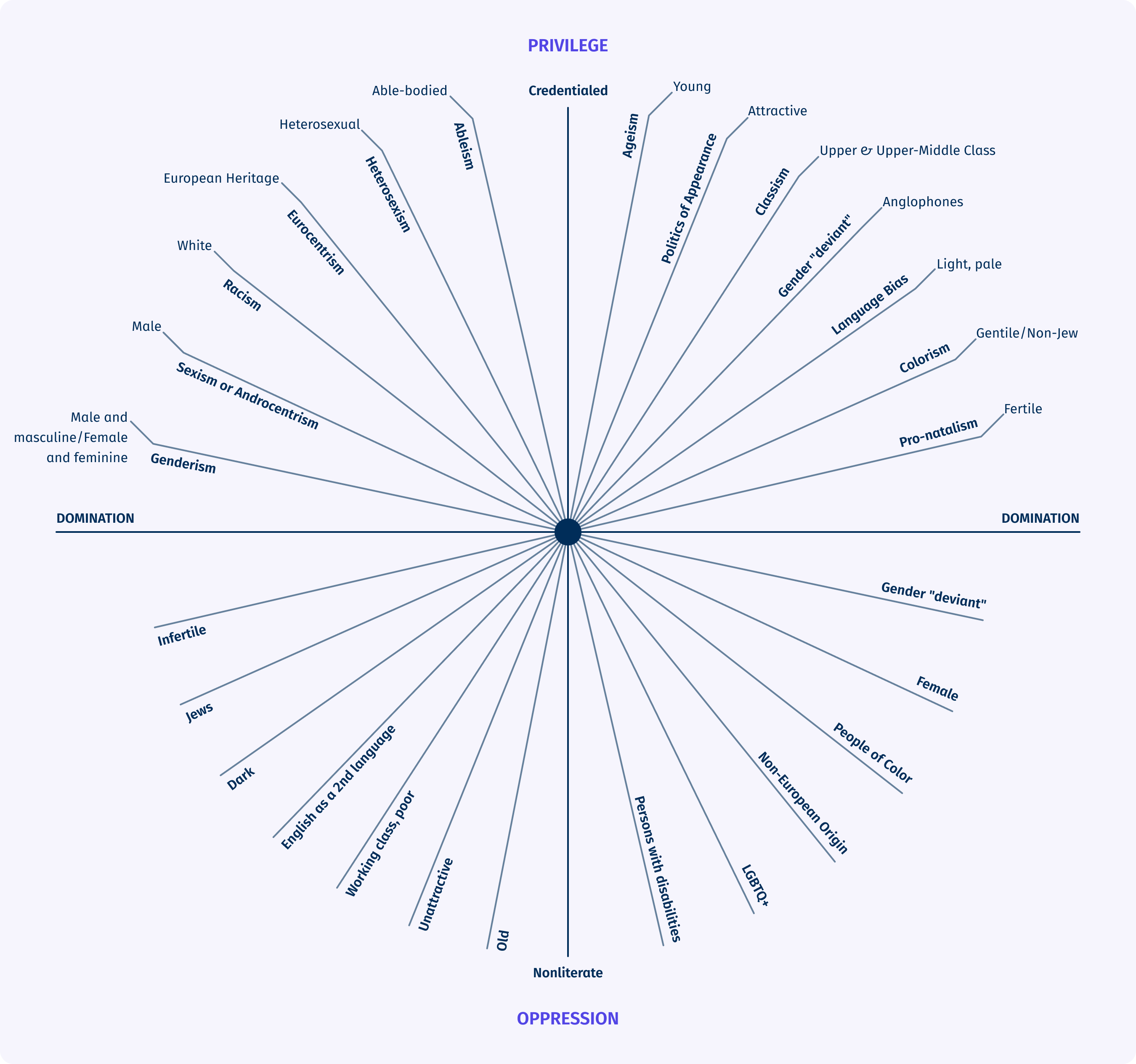

The below Intersecting Axes of Privilege, Domination, and Oppression diagram, which has been adapted from Kathryn Pauly Morgan’s model, shows what privilege means.

Those at the top of the circle indicate the dominant groups in our society, and those below are often people who face discrimination and oppression. You may identify with aspects from both sides.

But if you identify with more on the top of the circle, you’re much higher on the privilege spectrum. It’s important to note that one form of privilege doesn’t cancel out the other one.

All these aspects add up to form the circumstances you are in – that’s what intersectionality is and why putting people in boxes doesn’t work.

It’s also not about making sure that privileged people experience the same oppression as underrepresented groups - that completely defeats the purpose of equity.

It’s about making sure that we have fair processes and systems so everyone can benefit regardless of their circumstances or identity. But we can only do this once everyone recognizes where their privilege is giving them an unfair advantage, and we can make sure no one group has power over another.

As an educated, middle-class, South Asian woman, I recognize privilege. And until we build a community of allies who are comfortable stepping up and organizations who recognize the work they still have to do, I will continue to speak up.

Especially for those who are tired, those whose voices are not being heard, those who have less privilege than me, and those scared of what might happen if they speak.

Racism, diversity, and inclusion in the workplace: It's time to get uncomfortable, to get comfortable

If you want to become an active ally, here are a few things you can do:

- Look out for calls of support from people in marginalized groups. Amplify their voices and share their work.

- No one wants a savior, so any advocacy work you are doing, make sure it isn’t in isolation, and you’re speaking to the communities you’re supporting. Check-in with people and make sure it aligns with what they are trying to achieve.

- Remember that the community that you’re going to be an ally for should either be better off with your involvement or at the very least stay the same. You shouldn’t be there draining their resources, asking for freebies, or harassing them for educational conversations without giving something back.

- Many of us who belong to marginalized groups are often exhausted and rarely switch off. It can be emotional to keep calling out poor practice, so as an ally, you can help by educating others in your network and calling it out as well – it shouldn’t always be left to the people from marginalized communities calling out bad practice or behavior.

- When people share their emotional experiences, don’t pressure them to release names of individuals or the organization they may have referenced if they are not comfortable doing so. It might be painful to read but acknowledge that the conversation isn’t about you. Be supportive and ask how you can help.

It’s not easy being an active ally. It takes time, education, and not being scared of making mistakes.

It’s not enough saying that you’re not a racist, sexist, ageist, homophobic, etc, you have to be actively anti against these behaviors.

As communicators and often the people who hold the ‘pen’ in organizations we should be leading by example.

We’re going to talk more about allyship and other areas of diversity, equity, and inclusion at the A Leader Like Me Diversity of Action conference on 23 March.

All sessions are available on-demand, so if you can’t attend the whole day, you can watch back for up to 12 months. Tickets available from https://aleaderlikeme.com/conferences/div-in-action-conference/.

Here's another great article by Advita: Look around you. How many women of color leaders do you see? It's time for action, not words.